Follow the link below to see the work done by Rollo, G; Giménez, F; Peralta, A. & Yamuni, M.

miércoles, 6 de noviembre de 2013

The 70's: Punk Subculture

Follow the link below to see the work done by Natale, S; Tarsitano, F. & Moita, M.

Etiquetas:

counterculture,

music,

punk,

UK,

USA

Music in the 60's & 70's: Pop & Beat

Follow the link below to see the work done by Batiz, A., Pavilonis, M & Espósito, S.

http://prezi.com/haeyjehibxob/pop-beat-60-70/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy

Etiquetas:

20 century,

counterculture,

Culture,

music

The 50's & 60's in Music :Rock and Roll

Follow the link to see this work by Caveda, M, Tacconi, G, Irazu, L. & Puente, R.

sábado, 26 de octubre de 2013

The War Poets revisited: a modern-day response to 1914

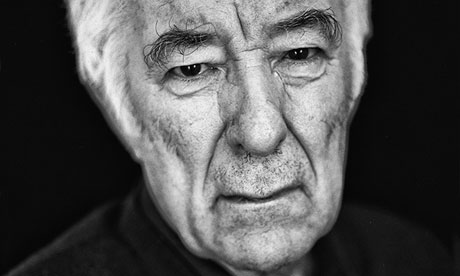

To mark the centenary of the first world war, poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy invited poets to respond to the poetry, letters and diary entries from the trenches and the home front – including Seamus Heaney, whose specially written poem is posthumously published here for the first time.

Follow the link to read The Guardian's article and the poems

sábado, 5 de octubre de 2013

Women Rights & Feminism

by Romina Puente, Gabriela Tacconi, & Martina Caveda.

Follow the link to see the presentation: http://prezi.com/dekbwqejqt8k/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy&rc=ex0share

Opt Art, Pop Art & Minimalism

Follow the link to see the complete presentation: http://prezi.com/-hrgbgnl7j4b/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy&rc=ex0share

domingo, 29 de septiembre de 2013

Beat Generation in Literature, Flower Power and Counterculture

Work done by Espòsito, Pavilonis & Batiz

Follow the link:

http://prezi.com/xsmaxretutvg/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy&rc=ex0share

Etiquetas:

Art,

Beat Generation,

Civil Rights ;Vietnam War,

Cold War,

Hippie,

Politics

viernes, 27 de septiembre de 2013

Abstract Impressionism

To see the complete presentation, follow this link:

http://prezi.com/ev--m8fo3trf/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy

Prepared by Tarsitano, Casadidio, Natale & Moita

lunes, 16 de septiembre de 2013

Civil Rights Movement

done by Rollo, Pereyra, and Mora

Etiquetas:

Civil Rights ;Vietnam War,

counterculture

lunes, 2 de septiembre de 2013

|

| Seamus Heaney, photographed at his home in Dublin in 2009: ‘Behind the unforced charm he was one of the most formidable critical intellects of his day.’ Photograph: Antonio Olmos

My first thought on hearing the immeasurably sad news of Seamus Heaney's death was a sensation of a great tree having fallen: that sense of empty space, desolation, uprooting. Heaney's place in Irish culture – not just in Irish poetry – was often compared to that of WB Yeats, particularly after he followed Yeats in winning the Nobel prize in 1995. He possessed what he himself ascribed to Yeats, "the gift of establishing authority within a culture". But whereas Yeats's shadow was seen, by some of his younger contemporaries at least, as blotting out the sun and stunting the growth of the surrounding forest, Heaney's great presence let in the light. Part of this was bound up in his own abundant personality. Generosity, amplitude and sympathy characterised his dealings with people at every level, and he was the stellar best of company. It was as if he had learned the lesson prescribed (though not really followed) by Yeats: that the creative soul, "all hatred driven hence", might recover "radical innocence" in being "self-delighting, self-appeasing, self-affrighting".

But behind the marvellous manner, unforced charm and wicked hoots of laughter he was one of the most formidable critical intellects of his day, a powerfully subtle analyst of political and social nuance, and the possessor of intellectual antennae that let nothing past them. Living in Ireland and being world-famous was not an unmixed blessing – he described the effects of winning the Nobel as "a mostly benign avalanche" – and he knew how to elegantly evade the occasional begrudgery of others and withdraw into his own resources, sustained by a beloved family life. The distinctiveness of his poetry was unmistakable: a Heaney poem carried its maker's mark on the blade. So was the immense labour that went into the deceptive simplicity of his early collections (throughout his writing career he drew terrific metaphors and images from an extraordinary range of physical work practices). And part of the impact of that early work lay in his use of violence.

That this was often done by implication made it no less shocking; the authentic lifting of the hairs on the back of the neck that I still remember when I opened North (1975), with its exploration of the archaeology of atrocity, was replicated in reading Station Island (1984), with its extraordinary title poem tracing a ghostly Dantean journey through the shades of Irish history, meeting with the dead. This culminates in a visionary encounter with Joyce ("His voice eddying with the vowels of all rivers/ came back to me, though he did not speak yet,/ a voice like a prosecutor's or a singer's,/ cunning, narcotic, mimic, definite"), and Joyce spoke to Heaney in more ways than one. Listening to him on Desert Island Discs some years ago, I waited for him to choose Yeats's poems as his elected book, only to hear him demand Ulysses instead; on reflection I was not surprised. His own capaciousness was Joycean.

Like Joyce, Heaney's erudition was immense, and his lectures on literature at Oxford, Harvard and worldwide made wonderful reading and unparalleled listening. They illustrate his openness to world literature and classical history as well as his deep love of unexpected English poets such as Clare and Wordsworth – and his affinity with writers from eastern Europe, Osip Mandelstam above all. "There is an unsettled aspect to the different worlds they inhabit," he wrote in The Government of the Tongue(1988), "and one of the challenges they face is to survive amphibiously, in the realm of 'the times' and the realm of their moral and artistic self-respect." This carried – as he himself pointed out – a resonant echo for a poet afflicted by "the awful and demeaning facts of Northern Ireland's history". He lived in Dublin but never evaded those "facts" of his native territory. Indeed, part of Heaney's immense achievement was to use and expand that "awfulness" and its relation to the creative spirit and artistic commitment, using implication rather than assertion – whether in the haunting parallels and allegories of North, or in later poems like From the Frontier of Writing and From the Republic of Conscience.

The note is there also in his wonderful last collection, Human Chain(2010), where one is pulled – yet again – in the wake of a writer able to push out the boat into a limitless sea. But what struck me most in reading it, along with the almost daunting economy of line, was a whispering sense of elegy – not just because many of the poems were dedicated to the dead, but also because they looped back to his earliest images of pen nibs, farm routines, animal life, the rituals of neighbourhood, and love. This sense of an ending was perhaps a sign of poetic prescience.

At the time of his death, though, I come back to the image of the death of a tree. I remember now that he wrote about this himself – both in a marvellous 1985 essay on the work of Patrick Kavanagh, and then in a sonnet sequence, Clearances, in memory of his mother. The tree in question grew from a chestnut which his aunt planted in a jam jar in 1939, the year of Heaney's birth; it flourished, was transplanted to the garden, became a fully sized tree "that grew as I grew" and came to symbolise his own developing life – until, in his early teens, the family moved away from the house and the new owners cut it down. The absence of the tree then created in Heaney's mind "a kind of luminous emptiness". He now identified, he wrote, with "preparing to be unrooted, to be spirited away into some transparent, yet indigenous afterlife". This is the thought that he put into Clearances (whose final sonnet is below), and I think of it now as I remember the marvellous spirit of a great poet who was also a great man.

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place In our front hedge among the wallflowers. The white chips jumped and jumped and skited high. I heard the hatchet's differentiated Accurate cut, the crack, the sigh And collapse of what luxuriated Through the shocked tips and wreckage of it all. Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole, Its heft and hush became a bright nowhere, A soul ramifying and forever Silent, beyond silence listened for.

Acceptance of his Nobel Prize lecture: http://www.nobelprize.org/mediaplayer/index.php?id=1506

|

viernes, 12 de julio de 2013

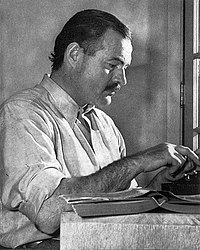

For Whom the Bells Toll and the Spanish Civil War

For Whom the Bell Tolls is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1940. It tells the story of Robert Jordan, a young American in the International Brigades attached to a republican guerrilla unit during the Spanish Civil War. As a dynamiter, he is assigned to blow up a bridge during an attack on the city of Segovia. Hemingway biographer Jeffrey Meyers writes that the novel is regarded as one of Hemingway's best works, along with The Sun Also Rises, The Old Man and the Sea, and A Farewell to Arms.

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) takes place during the Spanish Civil War, which ravaged the country throughout the late 1930s. Tensions in Spain began to rise as early as 1931, when a group of left-wing Republicans overthrew the country’s monarchy in a bloodless coup. The new Republican government then proposed controversial religious reforms that angered right-wing Fascists, who had the support of the army and the Catholic church.

After a strong Communist turnout in the 1936 popular elections, the Fascist army commander Generalísimo Francisco Franco initiated a coup in an attempt to overthrow the Republican government. Unexpectedly, the key cities of Madrid and Barcelona remained loyal to the Republic. This divide marked the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, a conflict between the right-wing Fascists (Nationalists) and the left-wing Republicans (Loyalists), a large number of whom were Communists. Violence exploded all over Spain, and both sides committed atrocities. Many western countries saw the Spanish Civil War as a symbolic struggle between fascism and democracy. Eventually, the superior military machine of the Fascist alliance prevailed, and the war ended in the spring of 1939.

During the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway was involved in the production of two Loyalist propaganda documentary films. Later in the conflict, he served as a war correspondent for the North American Newspaper Alliance. For Whom the Bell Tolls expresses Hemingway’s strong feelings about the war, both a critique of the Republicans’ leadership and a lament over the Fascists’ destruction of the earthy way of life of the Spanish peasantry. The novel is set in the spring of 1937, at a time when the war had come to a standstill, a month after German troops razed the Spanish town of Guernica. At this point, the Republicans still held out some hope for victory and were planning a new offensive. For Whom the Bell Tolls explores themes of wartime individuality, the effects of war on its combatants, and the military bureaucracy’s impersonal indifference to human life. Most important, the novel addresses the question of whether an idealistic view of the world justifies violence.

Hemingway’s novels are known for portraying a particular type of hero. Critic Philip Young famously termed this figure a “code hero,” a man who gracefully struggles against death and obliteration. Robert Jordan, the protagonist of For Whom the Bell Tolls, is a prime example of this kind of hero. The tragedy of the code hero is that he is mortal and knows that he will ultimately lose the struggle. Meanwhile, he lives according to a code—hence the term code hero—that helps him endure a life full of stress and tension with courage and grace. He appreciates the physical pleasures of this world—food, drink, sex, and so on—without obsessing over them.

Hemingway is particularly known for his journalistic prose style, which was revolutionary at the time and has influenced countless writers since. Hemingway’s writing is succinct and direct, although his speakers tend to give the impression that they are leaving a tremendous amount unsaid. This bold experimentation with prose earned Hemingway the 1953 Pulitzer Prize and 1954 Nobel Prize for Literature for his most popular work, the novella The Old Man and the Sea (1952).

Although Hemingway wrote several more novels afterward, he was never again able to match the success of The Old Man and the Sea. In the late 1950s, the combination of depression, deteriorating health, and frustration with his writing began to weigh heavily on him. His depression worsened, and in July 1961, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in Ketchum, Idaho. Although Hemingway’s long career ended sadly, his novels and short stories remain as popular today as ever before, and he maintains a reputation as one of the most innovative and influential authors of the twentieth century.

Follow this link to watch an Open Yale University lecture on the novel and the context. It`s hightly recommended!!!

Etiquetas:

Hemingway,

Literature,

Spanish Civil War

miércoles, 10 de julio de 2013

lunes, 1 de julio de 2013

lunes, 17 de junio de 2013

Ireland: "The Troubles"

|

| Photo: Two masked gunmen (Pacemaker Press Intl) |

The Troubles

1968 - 1998

The conflict in Northern Ireland during the late 20th century is known as the Troubles. Over 3,600 people were killed and thousands more injured.

Over the course of three decades, violence on the streets of Northern Ireland was commonplace and spilled over into mainland Britain, the Republic of Ireland and as far afield as Gibraltar.

Several attempts to find a political solution failed until the Good Friday Agreement, which restored self-government to Northern Ireland and brought an end to the Troubles.

The conflict in Northern Ireland during the late 20th century is known as the Troubles. Over 3,600 people were killed and thousands more injured.

Over the course of three decades, violence on the streets of Northern Ireland was commonplace and spilled over into mainland Britain, the Republic of Ireland and as far afield as Gibraltar.

Several attempts to find a political solution failed until the Good Friday Agreement, which restored self-government to Northern Ireland and brought an end to the Troubles.

viernes, 14 de junio de 2013

Ireland: The Road to Partition

Our guest from the UK, Blair (Language Assistant , British Council) has explained some history of his country (Northern Ireland) in our class.

We have worked on this subject in several occassions, and these are our old posts :

http://lenguaycultura2isfd97.blogspot.com.ar/2011/06/ireland-road-to-partition.html

Next Monday 24th, we`ll have a debate class monitored by Blair, so you can use these old posts to read about the subject.

jueves, 9 de mayo de 2013

Obras de Dalí, Picasso y Miró en La Plata

Por primera vez se exhibirán en una misma exposición numerosas obras de estos tres referentes del arte del siglo XX

Desde el próximo sábado 11 de mayo podrá visitarse en el Teatro Argentino la exposición “Dalí, Picasso, Miró: los españoles inmortales”. Esta muestra está compuesta por series de esculturas, platas, grabados, efectos visuales, litografías y linografías de estos tres grandes representantes del arte universal.

Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) es uno de los máximos referentes del surrealismo. Las obras incluidas en esta exposición, realizadas entre 1950 y 1980, fueron provistas a coleccionistas argentinos por Enrique Sabater, amigo del matrimonio Gala-Dalí.

En tanto, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) fue uno de los mayores artistas del Siglo XX. Pintor, grabador, impresor, ceramista y escultor, abordó además otros géneros como la ilustración de libros y el diseño de escenografías y vestuarios teatrales. Esta muestra está conformada también por litografías de Joan Miró (1893-1983) incluido entre las máximas figuras de la vanguardia española.

Las entradas están disponibles en las boleterías del Teatro (calle 51 entre 9 y 10), de martes a domingos, de 10 a 20. Para realizar visitas guiadas, comunicarse al Tel. 429-1745, de lunes a viernes, de 9 a 15.

¡IMPERDIBLE!!!

Etiquetas:

Art,

artists,

World War I; Cubism

martes, 30 de abril de 2013

'The Great Gatsby'

Baz Luhrmann's film of The Great Gatsby looks set to entertain, but it's Fitzgerald's life story that has to be seen to be believed.

Novel vision … (from left) Leonardo DiCaprio, Carey Mulligan, Joel Edgerton and Tobey Maguire in the Great Gatsby. Photograph: Allstar/Warner Bros/Sportsphoto Ltd

You can't open a newspaper these days without finding someone writing about F Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. I'm not complaining. Gatsby is the novel – almost a prose poem – I reread every year, and I never tire of its backstory. Although everything I've seen about Baz Luhrmann's forthcoming film fills me with anxiety, I'll be among the first to go and see it. Cinema and Fitzgerald could make an ideal marriage. Why shouldn't a movie director re-imagine 1920s West Egg and give us his reinterpretation of what Fitzgerald christened "The Jazz Age"? It can't, or won't, be the novel, but it might capture something of the madness in which Fitzgerald found himself.

The writer was great that way. A party animal with a line in champagne zingers; endlessly quotable; completely at one with the zeitgeist; a literary artist whose obiter dicta became the soundtrack of his times. For instance: "There are no second acts in American lives." And: "All good writing is swimming under water and holding your breath." And perhaps most famous of all, the last line of The Great Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

We're going to read a lot of Fitzgerald quotations these next few weeks. Fitzgerald's admirers will be delighted that he is getting some long overdue recognition, but sad, too, perhaps. When he died in Hollywood in 1940, Fitzgerald was almost completely forgotten. His funeral was attended by just 30 people, including his editor Maxwell Perkins. Sales of his books had virtually dried up. His publishers, Scribners, still had unsold stock from the first printing of Gatsby. He had lived the American dream, and it had turned into a waking nightmare.

But perhaps Fitzgerald's life and work is compelling precisely because it answers, in an archetypal way, what we, the reading public, expect the career of a genius to look like. Consider the bare bones of his story. Comfortable beginnings in St Paul, Minnesota, the heart of the midwest. His mother reports, appropriately, that the boy's first word was "up". First stirrings of the writer's ambition. He moves into the fast track of his society, pursuing literary goals, and goes to Princeton University. Drops out; falls in love and is rejected; writes a novel that's turned down; goes to the battlefields of France; returns to the USA with no prospects. Then ... 1919-1920: his annus mirabilis. Revises his unpublished work. This Side of Paradise is accepted by Scribner, and is published to huge acclaim. Now his sweetheart, Zelda Sayre, agrees to marriage.

Scott and Zelda lead rock star lives in the Manhattan of the 1920s. Burning with ambition for his art, Fitzgerald completes a book whose many rejected titles include Trimalchio in West Egg, the novel the world knows as The Great Gatsby. There's an added myth about its publication: Gatsby did not flop, as is often claimed; it just didn't do as well as had been hoped. TS Eliot, for one, wrote: "It seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James." It was only in comparison with Fitzgerald's astounding debut that it seemed to fail.

Thereafter, Fitzgerald went into a long tunnel of decline, a decade he later described in a controversial sequence of Esquire articles as "The Crack-Up", a rare text recently republished by Capuchin Classics. In search of that elusive "second act", he moved to Hollywood, published Tender Is the Night, a novel that baffled the critics, and began his final unfinished masterpiece, The Last Tycoon. Then dies, aged 44; is forgotten, but lives on through Gatsby. It's a literary life for the ages.

In outline, the F Scott Fitzgerald story is the movie you might want to see. Baz Luhrmann's version will be entertaining. It won't be Gatsby, the novel. But never mind. Many new readers will be inspired to discover the miracle of Fitzgerald's prose, and the strange subtlety of his vision. In 1925, Gatsby was ahead of its time, and almost too prescient. Now, it seems perfectly in harmony with the deepest and darkest chords in American life. That's why, for some, including this writer, it remains the greatest American novel of the 20th century.

Robert Mc Crum -The Guardian, UK

Premiere in Argentina: 16th May- La Plata: Cinema La Plata

Etiquetas:

Lost Generation,

The Great Depression;History,

WWII; Art

lunes, 29 de abril de 2013

When flappers ruled the Earth

The wild women of 1920s dance didn't just get everyone doing the Charleston and the Grizzly Bear. Stars like Josephine Baker and Tallulah Bankhead also played a pivotal role in women's emancipation

|

| The Nefertiti of now' ... Josephine Baker at the Casino of Paris in 1939. Photograph: Lipnitzki/Roger Viollet/Getty.

In 1908, wearing little more than a jewelled breastplate and a transparent skirt, the Canadian dancer Maud Allan stormed the fortress of British proprieties with her solo work, The Vision of Salomé. Allan danced an audacious choreography of desire, her body "swaying like a witch, twisting like a snake, and panting with [a hypnotic] passion", according to one dazed viewer. But while several theatres outside London barred Allan's performance as indecent, to her legions of women admirers, she was an inspiration. Margot Asquith, wife of the Liberal PM, was among those who saw Allan's dancing as a liberating expression of female sexuality.The early decades of the 20th century were an exhilarating battleground for women, with key gains made in political and legal reform. But women were also testing out another arena of emancipation: their bodies. As fashions grew simpler and skirts rose higher, reaching knee-length by the late 1920s, women found new physical freedoms – or, at least, those with sufficient money and time to take advantage of them.

In contrast to their bustled, draped and corseted grandmothers, they could feel the sun and wind on their limbs; they could run, stride and ride a bicycle with ease. They could also dance – and it's surely no coincidence that this was an era obsessed with dancing. From the barefoot ecstasies of Isadora Duncan, whosefree, expressive dancing struck a blow against the corseted rigours of classical ballet, to the collective "jazzing" of the 1920s, dance came to play a surprisingly emblematic role in the story of women's liberation.

The impact of Allan's Salomé spread far beyond theatre. To one rightwing politician, Noel Pemberton Billing, its eroticism was nothing less than an incitement to female depravity, specifically lesbianism. A decade later, with Britain at war, Billing published an article in his magazine Vigilante, accusing Allan of being key to a perniciously widespread "cult of the clitoris", and symptomatic of the unpatriotic decadence that was undermining the upper echelons of British society.

Even if Allan wasn't driving women to Sapphic wickedness, she was, in the words of another commentator, "promoting a dangerous tendency to dancing". And it wasn't just on the stage, but on the dancefloor, too, that women were displaying an alarming lack of modesty, with the social dances that began spreading through the west just before the first world war. Driven by the rhythms of American ragtime, the Bunny Hug, the Turkey Trot and the Grizzly Bear triggered a riotous deviation from the formality of the ballroom.

These encouraged dancers to kick up their feet, rock crazily from side to side and lock their swaying pelvises together. In 1914, the Vatican felt compelled to issue a formal denunciation of their suggestive, animalistic moves. To the young and very aristocratic British socialite Lady Diana Manners, these ragtime dances were part of a new "budding freedom", a sign that "Victorianism" had finally lost its grip.

Nightclubs had begun to appear in London in 1912 and, whenever Manners was able to evade her chaperones, these dark and crowded basements promised a cocktail of illicit thrills: smoking cigarettes, wearing lipstick, drinking Pink Ladies – and dancing. Her own expertise on the floor had been fuelled by a year of formal training in ballet and Russian folk dance. The physical poise she acquired wasn't just unusual for a woman of her class, though; it also provided a necessary boost to her confidence after the war, when she further flouted tradition by embarking on an acting career. Not only did this take her to Broadway, it also allowed her to support her husband, Duff Cooper, through his first years as a politician.

In the 1920s, ragtime was superseded by the wayward jangle and bounce of the Charleston and by the pert, buttock-flourishing naughtiness of the Black Bottom. Zelda Fitzgerald, famously the inspiration for her husband F Scott's fictional flapper heroines, was also a wicked exponent of the decade's jazz dances. The celebrity myths that accumulated around the Fitzgeralds were fed by stories of Zelda lifting her skirts high above her waist to emphasis the sway of her hips – and the flash of what Ernest Hemingway was pleased to call her "long nigger legs".

If dances were getting wilder, so too were morals. Between 1914 and 1929, the divorce rate doubled in the US and surveys reported that premarital sex was rising even faster. The promiscuity of young women caused alarm, particularly in Britain where, after the carnage of the war, it was estimated that only one in 10 were likely to find a husband and settle down to marriage and motherhood. As early as 1919, sympathy for their plight ebbed as the press began to speculate about the kinds of selfish, destabilising pleasures these single young women might be indulging in. The Daily Mail warned that the number of "superfluous" females could be a "disaster to the human race".

Dancing continued to be a lightning rod for public concern. In 1923, when Tallulah Bankhead came to London to advance her acting career, it wasn't just the delicious huskiness of her Alabama accent or the fizz of her personality that clinched her success. It was the topicality of the play in which she made her debut. The Dancers, written by Gerald du Maurier and Viola Tree, dramatised the arguments for and against liberated 1920s flappers through the stories of two very different dance-mad women. Bankhead's character Maxie was a professional cabaret artist whose dancing symbolised her independence; she earned her own money, and made her own way in the world. Her opposite number Audry, however, was a socialite whose addiction to dancing led only to a neurotic netherworld of nightclubs, cocktails and sex.

The moral chaos of Audry's world was captured in a picture painted by the Scottish artist John Bulloch Souter in 1926. Titled, starkly, The Breakdown, it showed a naked flapper dancing the Charleston to the accompaniment of a jazz saxophonist. The latter was seated astride a fallen statue of Minerva, goddess of wisdom; the fact that he was also black contributed to the public furore that got Souter's painting forcibly removed from the walls of the Royal Academy in London.

Race was another taboo being broken, as the era saw a mass emigration of black American musicians and dancers into the major cities of Europe.Ada "Bricktop" Smith, a cabaret singer from West Virginia, became doyenne of the Paris nightclubs, giving Charleston lessons to everyone from the writer and heiress Nancy Cunard to the Prince of Wales. And when a skinny chorus girl from St Louis called Josephine Baker was shipped over to Paris in 1925 to perform in the fashionable Revue Nègre, her subversively inventive versions of jazz dance were hailed by artists and intellectuals as genius. Picasso called her the "Nefertiti of now" – and such was the impact of her dancing that she became elevated to an aesthetic ideal.

Having endured racial abuse and discrimination back home, Baker was now advertising beauty products that allowed white women to mimic her own glossy cropped hair, her burnished skin and supple silhouette. It was an astonishing turnaround for her. But it also demonstrated the power that the symbols of the jazz age – its clothes, music and dancing – had to cut across social barriers.

Alive and kicking ... a Charleston competition at the Parody Club, New York in 1926. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Alive and kicking ... a Charleston competition at the Parody Club, New York in 1926. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty

There is, of course, a less benign story to tell about the degree to which these symbols became commodified by the new billion-dollar advertising, fashion and beauty industries, and about the pressures they imposed. Young flappers may have thrown off the tyranny of the corset, but they discovered the new tyranny of dieting. A schoolgirl in Chicago tried to gas herself because her parents wouldn't let her bob her hair or shorten her skirts along with her classmates.

But to the American writer Dorothy Dunbar Bromley, the flapper represented a new spirit of emancipation. If women were to follow their "inner compulsion to be individuals", they had to throw off their shackling inheritance of obedience, whether to the puritanical tenets of old-schoolfeminism or to the sentimentalised duties of marriage and motherhood. It wasn't hardcore politics but, on the dancefloor at least, these women of the 1920s embodied Bromley's views. As they shimmied their shoulders and swivelled their hips, they were released into a brief but deeply subversive world – a world of freedom.

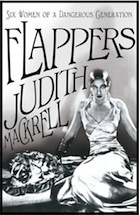

Flappers: Women of a Dangerous Generation

|

Etiquetas:

Art,

dance,

flappers,

Jazz Age,

World War I;

martes, 23 de abril de 2013

War Poets

World War I poets in England

For the first time, a substantial number of important English poets were soldiers, writing about their experiences of war. A number of them died on the battlefield, most famously Rupert Brooke, Edward Thomas, Isaac Rosenberg, Wilfred Owen, and Charles Sorley. Others including Ivor Gurney and Siegfried Sassoon survived but were scarred by their experiences, and this was reflected in their poetry. Robert H. Ross characterised the English "war poets" as a subgroup of the Georgian Poetry writers. Many poems by British war poets were published in newspapers and then collected into anthologies. Several of these early anthologies were published during the war and were very popular, though the tone of the poetry changed as the war progressed. One of the wartime anthologies was The Muse in Arms, published in 1917. Several anthologies were also published in the years after the war had ended. In November 1985, a slate memorial was unveiled in Poet's Corner commemorating 16 poets of the Great War: Richard Aldington, Laurence Binyon, Edmund Blunden, Rupert Brooke, Wilfrid Gibson, Robert Graves, Julian Grenfell, Ivor Gurney, David Jones, Robert Nichols, Wilfred Owen, Herbert Read, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon, Charles Sorley and Edward Thomas.

Interesting links: http://www.warpoetry.co.uk/firstWWarpoets.html

Log in to ecaths to get a copy of the poems and short stories we`ll study

sábado, 6 de abril de 2013

Welcome to Language & Culture II 2013!!!

Hello, Dear Students. This is the blog of our subject. This means will be used for complementing, sharing work and it`s our path to the subject's virtual platform called ecaths.

My piece of advice is to check this blog and the platform on (at least) a weekly basis, as you will be assessed for participating.

Here goes link to 2013 syllabus:

And this is an essay on High and Low cultures for the first classes:

Etiquetas:

Assignment,

Culture,

Lengua y Cultura 2,

syllabus

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)